Making a pygments lexer to syntax highlight SuperCollider code

Posted on .

This post is part of a series:Making an integrated book/website about music coding using MkDocs, LaTeX, and Python

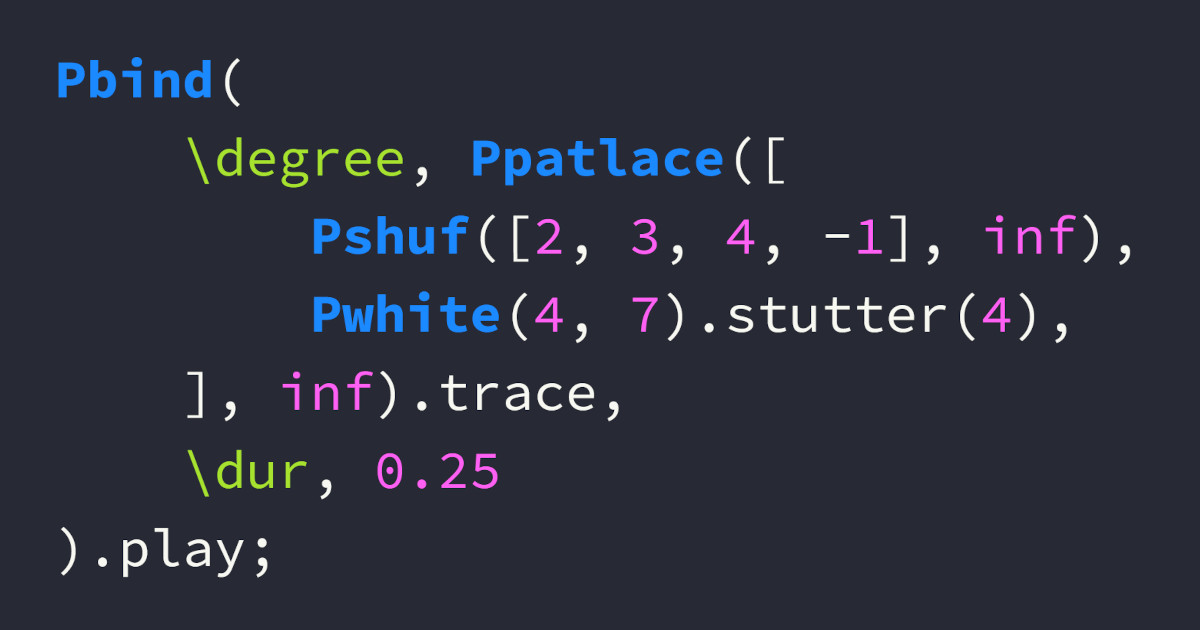

For my integrated book/website, it was important to present the 347 code examples in a reader friendly way. Proper syntax highlighting is essential, since it helps the reader distinguish the different elements of code examples. Highlighting SuperCollider code, however, turned out to be a bit of a challenge. I ended up reimplementing the pygments lexer for SuperCollider. Hopefully my implementation gets merged into pygments. As an alternative, it is available as a plugin on pypi, which includes an extra treat in the form of a dedicated color scheme.

Highlighting SuperCollider syntax with pygments

It was quite convenient for my book project that both mkdocs and LaTeX’s minted package use the same Python library called pygments for syntax highlighting. That meant that syntax highlighting would likely be consistent across the two versions of the book.

What was less convenient was the quality of highlighting when it came to SuperCollider code. In some highlighting engines, SuperCollider’s somewhat esoteric syntax isn’t as well supported as mainstream programming languages. In this case there were several limitations in the existing implementation of the SuperCollider lexer, so I decided to reimplement it to get more accurate results.

Hold on, what’s a lexer?

A lexer is a program that converts a given string of text into distinct lexical tokens which belong to different categories. Let’s say we have the following code:

apples + 7This simple expression contains five different lexical tokens:

apples, an identifier, likely the name of a variable.+, an operator.7, which is a literal, specifically a number.- Two instances of the space character, which is usually tokenized as whitespace.

When a lexer has grouped the characters of the string into these different tokens, we can apply different styling to them. Maybe we would like identifiers to be green, literal numbers to be red and bold, while operators are blue and italicised? Luckily, pygments comes with several predefined colour schemes.

By the way, lexical analysis is also involved when source code gets interpreted or compiled. Or, when an LLM needs to decode a prompt. Luckily, that’s outside the scope of this post… 😅

Writing a new lexer for pygments

There is a nice guide to developing new lexers for pygments which, admittedly, took me a bit of time to fully understand. But once you understand how the system works, it is clear that the lexical analysis engine in pygments does most of the heavy lifting for us. If you are comfortable with regular expressions and know the syntax of your language, putting together a lexer actually isn’t as difficult as it may sound.

Connecting text patterns with token categories

At the heart of lexical analysis in pygments is the mapping of a text search pattern to a token category. When we develop a lexer, we must supply the text pattern to look for, i.e. a regular expression pattern. For tokens, we can take advantage of pygments’s existing typology of lexical tokens.

Let’s look at a couple of examples: Class names and variables in SuperCollider.

- Class names in SuperCollider:

- Begin with an uppercase letter.

- May only contain word characters (a-z, A-Z, 0-9, and underscore).

- Examples include

SinOscandPbjorklund2. - In regex, we can match class names with the pattern

\b[A-Z]\w*\b.

- Variables scoped to a SuperCollider

Environment:- Begin with the tilde character (

~) followed by a lowercase letter. - May only contain word characters (aside from the initial tilde).

- Examples include

~freqand~steps. - We match these variables with the regex pattern

~[a-z]\w*\b.

- Begin with the tilde character (

We connect these patterns with the corresponding token categories using simple Python tuples:

# Class names

(r'\b[A-Z]\w*\b', Name.Class)

# Environment variables

(r'~[a-z]\w*\b', Name.Variable)Creating the lexer

To use the pygments lexing engine, we subclass the RegexLexer class. We tell our new lexer about our pattern-token mappings through the class variable tokens. Thus we have the basic structure of a functioning lexer:

class MyLexer(RegexLexer):

tokens = {

'root': [

(r'\b[A-Z]\w*\b', Name.Class),

(r'~[a-z]\w*\b', Name.Variable)

]

}In case you’re wondering, 'root' is a state that the lexer enters when beginning the analysis. We can define other states and move between them for various purposes, like matching escaped characters within a string, for instance. State management in a pygments lexer can be tricky to understand but is very useful when dealing with nested text patterns. Check out the documentation to learn more.

Matching SuperCollider syntax

The patterns I used to reimplement the lexer fall into the categories listed below. The lexer processes SuperCollider source code by moving through these token categories in sequence: whitespace, comments, keywords, identifiers, strings, numbers, punctuation, operators, and finally generic names. Any remaining unmatched text falls through to a catchall state that marks it as generic text.

tokens = {

'root': [

include('whitespace'),

include('comments'),

include('keywords'),

include('identifiers'),

include('strings'),

include('numbers'),

include('punctuation'),

include('operators'),

include('generic_names'),

include('catchall'),

],The lexer’s design follows the principle that more specific patterns should be matched before more general ones. This is why comments are processed before identifiers (so that code within comments isn’t mistakenly highlighted as separate tokens), and why special number formats like radix notation are matched before plain integers.

Note that, for instance, comments occur before identifiers. This is so that any text within a comment gets tokenized as belonging to a comment and not an identifier.

Most of these are relatively simple to implement, like single line comments, whitespace, punctuation, integers, etc. I go over some of the more intricate ones below.

Multiline comments

Comments in SuperCollider are actually slightly more complicated than you might think. SuperCollider allows nested multiline comments, which are rather tricky to match with regex alone.

/* This is a multiline comment

with /* another comment */ nested inside */Luckily, the pygments documentation shows exactly how to deal with patterns like this: We process the nested comments using recursion into a multiline comment state, which keeps the regex pattern matching quite simple:

'comments': [

(r'/\*', Comment.Multiline, 'multiline_comment'),

(r'//.*?$', Comment.Single),

],

'multiline_comment': [

(r'[^*/]+', Comment.Multiline),

(r'/\*', Comment.Multiline, '#push'),

(r'\*/', Comment.Multiline, '#pop'),

(r'[*/]', Comment.Multiline)

],When we encounter an opening /* while already inside a multiline comment, we push the current state onto a stack ('#push'). On a closing */, we pop from the stack ('#pop'). This allows us to properly handle arbitrarily nested comments.

Keywords and identifiers

Matching keywords is simple, provided you know which words to look for. Pygments provides a words function that takes a list of words and returns an optimised regex pattern that will match those words. I knew most of SuperCollider’s keywords and hunted through the documentation to find the rest. Along the way, I realized that a keyword isn’t just a keyword.

- In SuperCollider, the keywords

var,arg, andclassvarare declarations, in that they declare a variable or an argument. - Other keywords represent singleton constants, like SuperCollider’s

nil. - Some don’t fall into either category and can be classified simply as reserved keywords.

- Still others I have decided to not categorise as keywords at all, such as

pi, which is considered a float, andthisProcesswhich the SuperCollider documentation calls a “global pseudo-variable”.

'keywords': [

(words(('var', 'arg', 'classvar'), prefix=r'\b', suffix=r'\b'),

Keyword.Declaration),

(words(('true', 'false', 'nil'), prefix=r'\b', suffix=r'\b'),

Keyword.Constant),

(words(('const', 'context'), prefix=r'\b', suffix=r'\b'),

Keyword.Reserved),

],Identifiers

“Identifier” is a fancier term for the token category that pygments calls name. This includes class names, variable names, method and function names, etc. Lets look at an example:

SinOsc.ar(~freq)Here are three different kinds of identifiers:

SinOscis a class name that identifies (you guessed it) sine wave oscillators.aris the name of a (class) method which instantiates an audio rate UGen.~freqis the name of a variable, presumably holding a number to specify the oscillator’s frequency.

As we process all the identifiers like variables and class names with specific patterns inside the 'identifiers' state and other patterns in other states, the remaining bits of text are interpreted as generic name tokens in the 'generic names' state. These include local variable names, names of methods, word and binary key operators.

Here’s how the lexer handles different types of identifiers:

'identifiers': [

# Class names are capitalised

(r'\b[A-Z]\w*\b', Name.Class),

# Environment variable names are prefixed with ~

(r'~[a-z]\w*\b', Name.Variable),

# Built-in pseudo-variables

(words((

'thisFunctionDef',

'thisFunction',

'thisMethod',

'thisProcess',

'thisThread',

'this'),

prefix=r'\b', suffix=r'\b'),

Name.Builtin.Pseudo),

# Primitives (starting with underscore)

(r'_\w+', Name.Builtin),

# _ is an argument placeholder in partial application

(r'\b_\b', Name.Builtin.Pseudo),

],

'generic_names': [

# Remaining identifiers starting with lowercase

(r'[a-z]\w*\b', Name),

],Strings and characters

SuperCollider has several types of string-like literals that need different handling:

- Double-quoted strings (

"hello world") which can contain escape sequences. - Symbols (

'symbol'or\symbol) which are unqiue strings used for efficient comparison. - Character literals (

$aor$\n) representing single characters.

The lexer handles these with separate patterns:

'strings': [

# Double-quoted strings with escape sequence support

(r'"', String.Double, 'double_quoted_string'),

# Symbols - single-quoted or backslash notation

(r"'(?:[^']|\\[^fnrtv])*'", String.Symbol),

(r'\\\w+\b', String.Symbol),

(r'\\', String.Symbol),

# Character literal escape characters

(r'\$\\[tnfvr\\]', String.Char),

# Regular character literals (ASCII only)

(r'\$[\x00-\x7F]', String.Char),

],

'double_quoted_string': [

(r'\\.', String.Escape),

(r'"', String.Double, '#pop'),

(r'[^\\"]+', String.Double),

],The double-quoted string state handles escape sequences properly by using a separate state that matches escape patterns before returning to the main string content.

Numbers

SuperCollider supports various numeric formats that go well beyond simple integers and floating-point numbers. I personally never have felt the need to express musical parameters using radix 19, but perhaps others have. In any case, our lexer needs to handle:

- Special float constants designated by keywords

infandpi. - Radix notation for numbers in different bases (e.g.,

12r4A.ABCfor base-12 numbers). - Scale degree accidentals using sharp (

s) and flat (b) notation (e.g.,4s,7b2). - Scientific notation with optional type suffixes.

- Hexadecimal numbers with

0xprefix.

Here’s how these patterns are implemented:

'numbers': [

# Special float constants

(r'(\binf\b|pi\b)', Number.Float),

# Radix float notation (e.g., 12r4A.ABC)

(r'\d+r[0-9a-zA-Z]+(?:\.[0-9A-Z]+)?', Number.Float),

# Scale degree accidentals (e.g., 4s, 7b2, 3sb)

(r'\d+[sb]\d{1,3}\b', Number.Float),

(r'\d+[sb]{1,4}\b', Number.Float),

# Regular floats with optional scientific notation and type suffixes

(r'\d+\.\d+([eE][+-]?\d+)?[fd]?', Number.Float),

(r'\d+[eE][+-]?\d+[fd]?', Number.Float),

# Hexadecimal numbers

(r'0x[0-9a-fA-F]+', Number.Hex),

# Plain integers

(r'\d+', Number.Integer),

],The order matters here: The more specific patterns like radix notation and scale degrees need to be matched before the general integer pattern, otherwise 12r4A would be tokenized as the integer 12 followed by the identifier r4A.

Punctuation and operators

The patterns mentioned above mostly consist of alphanumeric characters. But like other

SuperCollider has a rich set of operators, including both symbolic operators and word-based operators. The lexer separates these into punctuation and operators:

'punctuation': [

(r'[{}()\[\],\.;:#^`]+', Punctuation),

(r'<-', Punctuation), # for list comprehensions

],

'operators': [

# Binary operators made with characters from the allowed subset

(r'[!@%&*\-+=|<>?/]+', Operator),

],The punctuation patterns handle structural elements like braces, parentheses, and semicolons, while the operator pattern matches sequences of symbolic characters that form binary operators like +, **, <=, etc.

An interesting aspect of SuperCollider is that many operators can be written in word form (like add, mul, div) and are synonymous with method names. Rather than treating these as operators, the lexer handles them as regular identifiers in the 'generic_names' state, which is consistent with how SuperCollider’s own IDE highlights them.

Styling the tokenized code

When a piece of text has been tokenized with a lexer, you can then format the code, i.e. apply color and styles to the text bits depending on their token type. There are many ways in which this can be done depending on framework choice. Pygments itself can do the formatting, and you can choose between multiple builtin styles.

I wasn’t completely satisfied with the builtin styles, so I decided to roll my own. Check out the code on GitHub if you like.

Creating custom SuperCollider styles

Pygments styles are Python classes that define color and formatting rules for different token types. I decided to provide two versions to support both dark and light themes, as the website allows the user to switch to and from dark mode. Taking inspiration from the SuperCollider IDE’s own syntax highlighting, my key design decisions were as follows:

- Class names get a bold, bright blue treatment to make them stand out as the primary building blocks of SuperCollider code.

- Environment variables (those prefixed with

~) are styled in bold orange/amber to distinguish them from regular variables. - Keyword declarations like

varandarguse a bold red color to emphasize declarations. - Numbers and constants share similar purple/magenta styling since they’re both literal values.

- Strings and symbols are differentiated: Strings are blue while symbols get the accent green color.

- Comments are italicised with a neutral color.

- Punctuation, operators, and generic names get a default color that doesn’t stand out.

The dark theme uses vibrant colors against a dark background reminiscent of popular code editors, while the light theme employs more muted but still clearly distinguishable colors suitable for printable documentation or bright environments.

To define a pygments style, we subclass the Style class. Pygments will look for a class variable called styles, a dictionary of token-to-color mappings.

class SuperColliderDark(Style):

'''

This style accompanies the SuperCollider lexer and is designed for use with dark themes.

'''

name = 'supercollider_dark'

colors = {

'primary': '#f8f8f2',

'accent': '#a6e22e',

'number': "#ff60f4",

'comment': "#a8cee0",

'class': '#1b89ff',

'env_variable': '#fd9d2f',

'keyword_declaration': '#de4d45',

'string': '#618bff',

'char': "#d84841",

'background': '#272822',

'highlight': '#575C3A',

}

styles = make_sc_styles(colors)Mapping colors and token categories

To create the mappings, a simple make_sc_styles function accepts a dictionary of colors and returns the token-to-color mappings:

def make_sc_styles(colors):

'''Create a SuperCollider styles dict from a dictionary of colors.'''

return {

Number: colors['number'],

Name: colors['primary'],

Text: colors['primary'],

Operator: colors['primary'],

Punctuation: colors['primary'],

Comment: f"italic {colors['comment']}",

Name.Class: f"bold {colors['class']}",

Name.Variable: f"bold {colors['env_variable']}",

Keyword: colors['accent'],

Keyword.Declaration: f"bold {colors['keyword_declaration']}",

Keyword.Constant: colors['number'],

String: colors['string'],

String.Symbol: colors['accent'],

String.Char: colors['char'],

}With this setup, the SuperColliderDark and SuperColliderLight style classes each define their own color palettes and then use this shared function to generate the token mappings. This ensures consistency between the light and dark themes and makes color adjustment easy without duplicated code.

Results and conclusion

The reimplemented lexer provides accurate and comprehensive syntax highlighting for SuperCollider code. It has been submitted as a pull request to the main pygments project, where generous feedback from a SuperCollider developer improved the implementation. While waiting for the upstream review process, the lexer is available as a standalone package on PyPI that can be installed and used immediately.

For my book project, this meant that all 347 SuperCollider code examples could be consistently and accurately highlighted across both the mkdocs web version and the LaTeX PDF version. The effort invested in creating a proper lexer paid dividends in the legibility of the technical content. This is open source development that makes sense: What started as a personal need for better syntax highlighting became a contribution that can hopefully benefit the wider SuperCollider community.

This post is part of a series: Making an integrated book/website about music coding using MkDocs, LaTeX, and Python

- Part 1: An integrated book and website

- Part 2: Converting markdown to LaTeX with md2tex

- Part 3: Making a pygments lexer to syntax highlight SuperCollider code (this post)

- Part 4: New MkDocs plugins for embedding and visualizing audio